Five years ago, Stanford History of Science Professor Londa Schiebinger was in Madrid and interviewed by some Spanish newspaper reporters. When she returned home, she put the articles through Google Translate and was shocked to see that she was repeatedly referred to as “he.”

Oops — of all the people for this to happen to. Schiebinger has spent the last three decades exploring the intersection of gender and science, and her current work on Gendered Innovations in Science Health & Medicine, Engineering, and Environment at Stanford University focuses on how to harness the creative power of “gender analysis” for discovery and innovation.

Google’s algorithmic fail became fodder for a case study on gender biases in machine learning, with Schiebinger inviting two experts in natural-language processing to a workshop at Harvard University. After listening for about 20 minutes, the one from Google said, “We can fix that!”

“Fixing it is great, but constantly retrofitting for women is not the best road forward,” Schiebinger states in her Gendered Innovations case study. “To avoid such problems in the future, it is crucial that computer scientists design with an awareness of gender from the very beginning.”

Such an issue may amount to no more than a minor bug for a business as big as Google. But a failure to consider diverse users in the design of a product at smaller firms like startups could seriously limit their financial future by overlooking or alienating potential markets and user needs — or even harming the business’s brand reputation.

Take Snapchat. In August, the image-messaging app introduced a filter that puts extremely slanted eyes, rounded cheeks and buckteeth on a face. In a blog post by Katie Zhu, a member of the product and engineering team at the publishing platform Medium, she said Snapchat called the filter “anime-inspired.”

“Anime characters are known for their angled faces, spiky and colorful hair, large eyes and vivid facial expressions,” Zhu wrote in her post “I’m deleting Snapchat, and you should too.” “This is quite literally yellowface, a derogatory and offensive caricature of Asians.”

“Fixing it is great, but constantly retrofitting for women is not the best road forward.”

– Stanford Professor Londa Schiebinger

This wasn’t the only instance in which Snapchat has sparked criticism within industry and from individual users over filters that superimpose racially stereotypical traits onto photos of faces. Four months prior, Wired wrote about how Snapchat released a “Bob Marley filter” on April 20, the day marijuana lovers celebrate their shrub of choice. The headline said it all: “Welp! Snapchat’s 420 Filter Celebrates Bob Marley with Blackface.”

The Venice-based startup issued a statement after the article appeared, explaining that the filter was created “in partnership with the Bob Marley Estate” to give fans a way to show their appreciation of the reggae legend. Snapchat has also spurred comments in mainstream press outlets such as Business Insider, and on sites like Medium and Quora, for a lack of transparency regarding its total number of employees and how many of them are women or minorities.

Yes, Snapchat’s popularity seems to be growing by the day. But it’s uncertain how much the firm can expand its user base beyond those over 25 and into the more lucrative demographic groups that advertisers desire. Moreover, systemic issues around diversity that get ignored early on just might grow into deal-breakers that make a hot, young startup less attractive to potential suitors in the years ahead.

That seems to be playing out at Twitter. On Oct. 27, the San Francisco public radio station KQED reported the startup’s plans to lay off 300 people, and how it may be tied to the company’s unresponsiveness to harassment by “trolls.” For KQED’s California Report, journalist Queena Kim quoted a Bloomberg analyst who described how Twitter’s user growth and advertising dollars are both flattening out, and how that may be a result of all the negative content.

Kim then spoke to a BuzzFeed reporter who said both Disney and Salesforce may have walked away as potential buyers in part because of Twitter’s seeming indifference toward offensive comments. Kim went on to explain how women and minorities who work at Twitter had brought the issue to the attention of senior management as far back as 2008, and how that leadership remains largely white and male.

The report ended with a comment by Kellie McElhaney, an adjunct faculty member at the Haas School of Business at the University of California, Berkeley: “This is an example of how lack of diversity is bad for business.”

(Since that report, Twitter announced several new measures aimed at curbing hate speech — although a New York Times article questions if features such as the ability to hide or report offensive posts will have any lasting impact.)

Data on Diversity … or Lack Thereof

While concerns about the underrepresentation of women and minorities in tech isn’t new, the heightened awareness of the problem can be traced back to October 2013, when Tracy Chou, a young female engineer at Pinterest, blogged about the absence of data on gender diversity in the industry.

Other luminaries of the valley, such as Eric Reis and Vivek Wadhwa, had already pointed out that the local tech community mostly consisted of white men. But Chou did something clever: Alongside her blog post on Medium, she set up an online repository and encouraged tech workers throughout the valley to count the number of female engineers at their companies and share them.

“Systemic issues around diversity that get ignored early on just might grow into deal-breakers that make a hot, young startup less attractive to potential suitors in the years ahead.”

She started by posting Pinterest’s stats: 11 female engineers out of 89 total at the time. Soon after, dozens of other tech firms contributed theirs, including Dropbox, Reddit and Mozilla. A few months later, Google publicly reported its figures on ethnic and gender diversity, and then Apple, Facebook, Twitter and other tech giants followed suit.

“Once all that data was out there, this thing which had been an open secret in Silicon Valley for a long time became known to the rest of the world as well,” Chou said on the Stanford Innovation Lab podcast. “It became a really big topic of conversation when people realized that these companies [that] are producing technology and products that everyone is using were so not representative in their workforces of the people that they were trying to serve.”

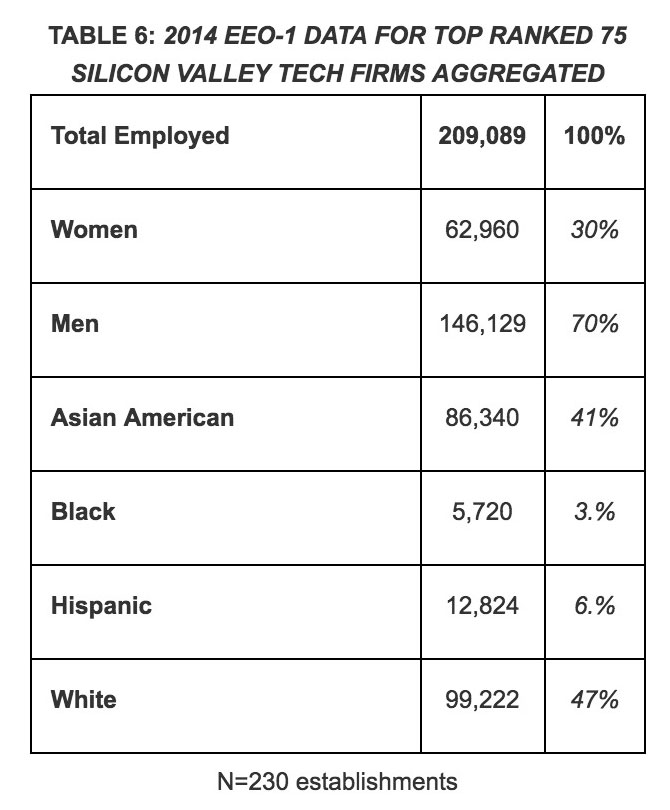

Recently, the U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission published a report on diversity in high-tech that summarized data on the race and sex of all employees at the top 75 tech firms in the valley (as ranked by the San Jose Mercury News in 2015). The data was pulled from government-mandated diversity reports, called “EEO-1” filings.

Of the nearly 210,000 employees across 230 work sites throughout the valley belonging to the top-ranked companies, here’s what the commission found: Seven out of 10 employees were men, while the percentages of black and Hispanic workers were 3 and 6 percent, respectively.

“What is striking in this table is the degree of sex and race segregation,” the report states. “Women comprise just 30 percent of total employment and Asian Americans and Whites comprise 88 percent of all employment.”

Study after study has found that more diversity is better for business. Just to cite one report from 2015, the business-consulting giant McKinsey & Co. examined proprietary data sets for 366 public companies and found that more diverse workforces performed better financially.

Specifically, companies in the top quartile for racial and ethnic diversity were 35 percent more likely to have financial returns above their respective national industry medians. Meanwhile, firms in the top quartile for gender diversity were 15 percent more likely to top their industry medians in returns.

“Given the higher returns that diversity is expected to bring,” the report concludes, “we believe it is better to invest now, since winners will pull further ahead and laggards will fall further behind.”

Earlier Interventions Needed

The glitch in Google Translate that converted references to Londa Schiebinger to “he” was based on the fact that phrases such as “he said” are more commonly found online than “she said.” Schiebinger’s case study on this fits into a category she calls “bias in big data,” and she has since discovered newer examples of unintentional bias in algorithms.

She notes, for instance, that Amazon’s same-day delivery service was unavailable for zip codes in predominantly black neighborhoods at one point. She also notes the now well-known example of Google’s photo app, which applies automatic labels to pictures in digital photo albums. Early versions of the app inadvertently identified African-Americans as gorillas. Google apologized, saying it was unintentional.

Specifically in the area of product design, Schiebinger discovered examples of likely gender bias in software at Pinterest and Apple:

- At Pinterest, she saw how the failure to consider men as users may have taken a financial toll. Between 2011 and 2015, Pinterest’s valuation rose from $200 million to $11 billion. Yet, only 29 percent of Pinterest users were men in 2014. “It is not only women who are left out, but also men. Pinterest is currently seeking to revamp its search algorithms to reach out to men,” Schiebinger said. “Products that incorporate the smartest aspects of gender and meet the needs of diverse user groups can open new markets and enhance global competitiveness.”

- When Apple released its HealthKit app in 2014, it boasted the ability to record blood pressure, daily steps and calories, respiratory rate and even blood-alcohol level. But it left out women’s menstrual cycles. Apple updated it a year later, but Schiebinger questioned the cost in terms of profit, poor publicity and team morale.

Tracy Chou now works on increasing diversity at tech companies through an organization called Project Include, which she co-founded with other influential women in the industry. They describe the project as “an open community working toward providing meaningful diversity and inclusion solutions.” Beyond tactics like anonymizing job-applicant resumés, Chou says Project Include offers comprehensive recommendations and is taking steps to put them into practice.

One is called Startup Include, where companies that participate commit to metrics that they will share with Project Include after three and six months to measure progress. Much like the tech industry itself, the project takes an open source and data-driven approach, with the goal of aggregating metrics across a cohort of firms and developing benchmarks.

“It’s much easier to change the course early on and set the right culture, than trying to steer a really massive ship later.”

– Tracy Chou, Project Include

“We’re focused specifically on tech startups, where we think there’s just so much opportunity to get things right from the beginning,” said Chou, who earned degrees in electrical engineering and computer science from Stanford. “It’s much easier to change the course early on and set the right culture, than trying to steer a really massive ship later.”

Among the startups working with Project Include are Asana, Clef, Managed by Q, Patreon, Periscope Data, PreK12Plaza, Puppet, Truss and Upserve. But just as success doesn’t happen overnight in the startup world, Chou says the effort to increase diversity in tech will require conviction and patience commensurate with the problem at hand.

“There isn’t a quick fix for diversity and inclusion,” she says. “It has to be prioritized on an ongoing basis and it takes a lot of hard work. But it’s worth the effort.”