It is raining on the first day of Stanford’s Entrepreneurial Thought Leaders Seminar series, and it couldn’t be more fitting for today’s speaker. David Friedberg is the CEO of The Climate Corporation (formerly WeatherBill), a weather insurance company. In fact, David came up with his original idea for WeatherBill on a rainy day in San Francisco.

On his daily commute through San Francisco, Friedberg noticed that rain regularly closed down a bicycle shop that caters to tourists. Soon after, Friedberg would go on to found The Climate Corporation on the observation that so many businesses are affected by the weather. But David Friedberg hates being called a founder. In fact, he says that when his venture capitalists introduce him as the “founder” of The Climate Corporation, he tells people, “Founder isn’t really a role. It’s really not a role that I like.”

Friedberg is a person focused on solving problems. He describes this as “revealing truth and fact,” and he doesn’t hang on to the founder title like others do. Instead, he is practical. He takes the executive position bluntly stating that “I’m the CEO of the company today, and I might not be the best CEO tomorrow.” He is blissfully truthful about his no nonsense role in the company.

He has built a multimillion dollar funded company in a short while, pulled everything together, and readily admits he would be ready to remove himself if/when he is no longer the right person for the job. That is a really intimidating statement to hear, especially coming from someone as obviously talented as Friedberg.

Listening to Friedberg, I sheepishly think of my own LinkedIn profile, where the title of “Founder” is plastered in at least one or two places in connection with some of my previous side projects. I am tempted to skirt over to my profile for some quick resume tidying, but then a question comes to mind: What is a founder?

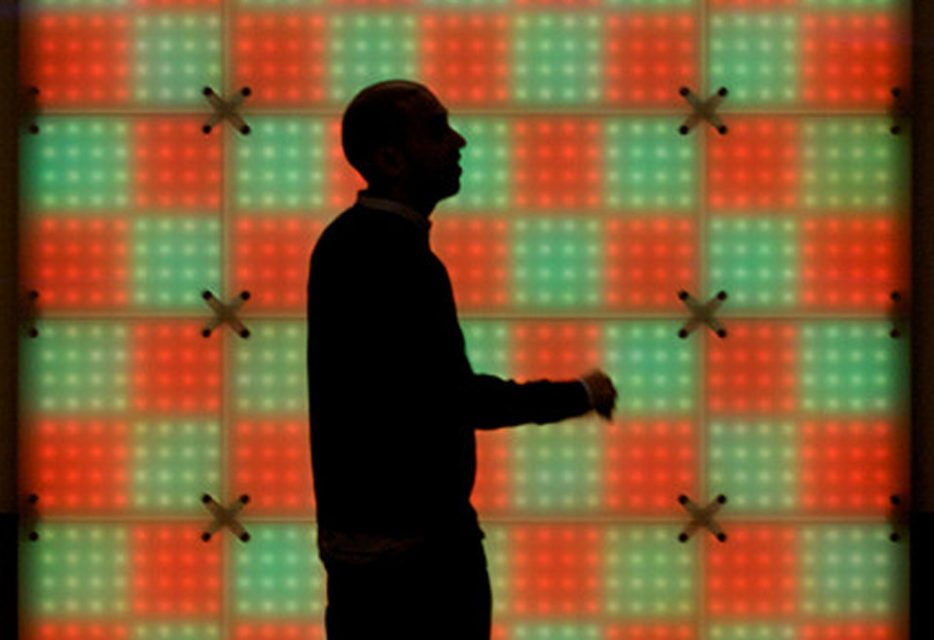

Continuing with his lecture, Friedberg projects two pictures on screen for the audience. One of the pictures is of a “rock star” founder, just having made his exit — an image commonly featured by Fast Company and Forbes. The other picture is of the archetypal “real” founder, sleep deprived, running on caffeine, and near the end of his rope.

Seasoned entrepreneurs, CEOs, professors and founders alike tell us that the “rock star” picture is a fantasy.

The former image is a Silicon Valley dream boy, a ubiquitous legend not only in the Valley, but also in pop culture. It is simultaneously the joke of Silicon Valley, while inadvertently being a false representation of the Valley and the entrepreneurial community at Stanford. Seasoned entrepreneurs, CEOs, professors and founders alike tell us that the “rock star” picture is a fantasy.

The second of David Friedberg’s pictures looks more like a Stanford computer science student scraping away at the last bugs in a systems assignment, or in Friedberg’s case, a startup. In fact the difference between the two might be minuscule. Students straining on Redbull aren’t much different than those founders pulling late nights on Starbucks. This latter image is a dose of reality, and Friedberg has some statistics to further the point.

According to Friedberg, the odds of starting a company and having it be worth $1 billion dollars in 49 months after founding are about 0.0006%. After accounting for average dilution, this is the equivalent of earning a $73,000 annual salary. But you also have a 67% chance of making absolutely nothing at all. The audience laughs at this, but are we convinced?

It seems there are more people in my Stanford class who are going to be “founders” than employees. I have more Silicon Valley business cards with “founder” on them than anything else. And how often do you hear the phrase “YC Founder” from Y-Combinator, Paul Graham’s premier accelerator? Sometimes I wonder how we have anything but single person LLCs in Silicon Valley. Stanford and Silicon Valley rightly lionize the act of taking initiative, but where is the line between taking initiative to solve real problems and taking initiative for initiative’s sake?

A trend of some of the friends/entrepreneurs I look up to most is to label themselves “janitor at Stealth Startup” on their LinkedIn profiles. It’s a humorous, self- deprecating poke at their predicament. Janitors clean up messes. It isn’t a frilly job, but a janitor’s role is indispensable. To put it simply, janitors solve problems.

“I don’t want to say be entrepreneurial,” says David Friedberg. “I want everyone in this room to walk away from this discussion today, reflective about what it is you want out of life and then make a choice that is based on some of the things that I am trying to tell you about today.”

As the lecture ends, the rain gives the crowd a break as they trickle from NVIDIA Auditorium on the Stanford campus. The crisp California evening air brings clarity, and I am reflecting on Friedberg’s advice.

And weighing a career in janitorial work.