On the final episode of season two, FRICTION podcast host and Stanford Professor Bob Sutton is joined by Rachel Julkowski, producer and Director of Marketing and Editorial for the Stanford Technology Ventures Program. Together, they share lessons learned from this season’s guests, and what each of us can do to battle friction within our organizations. Some of their big take-aways from this season include:

- Sometimes, the best thing you can do is slow down.

- When in doubt, look for the optimists.

- The best thing you can do for your team is to be an honest and transparent leader.

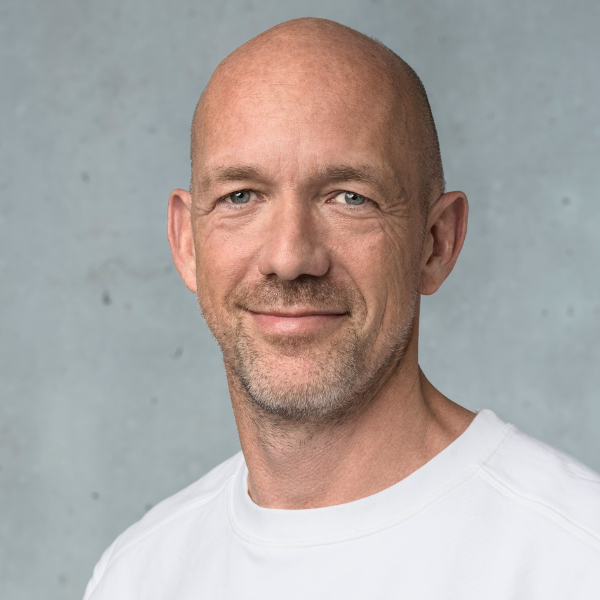

Bob Sutton: Hi, I’m Bob Sutton. I’m an organizational psychologist and Stanford professor, and this is the FRICTION podcast. Thanks for joining us on this podcast where we explore the ups and downs and ins and outs of organizational friction. Things can get a little dark when you stare directly into the messiness and muck of organizations. On this final episode of the season, my producer, Rachel Julkowski, joins me to try and channel some optimism and some hope.

Rachel Julkowski: So Bob, we’ve spent the last 11 episodes getting in the muck, talking with people about what it takes to both cure this organizational malaise and drag and frustration and also how we can kind of lend gasoline to the fire of friction when it’s good.

Bob: Right.

Rachel So tell us about your top reasons why friction is a good thing and how we should come to accept it, and harness it, and use it better to help us.

Bob: Well, so one of the first things that strikes me, and we just reviewed the 11 episodes, and it comes out one way or another in all of them is the notion that sometimes, when you’re racing ahead, you’ve just got to stop and think. Sometimes you gotta stop and gather your energy. Sometimes things are so screwed up that you have to just figure out something, what’s wrong and what’s gonna work. So one example in Nancy Koehn’s episode, she was talking about the Shackleton expedition and there were times when they didn’t know what the heck to do, when they were just too exhausted and they could’ve raced ahead, but they would just sort of slow down. And another thing which sorta combines the slowing down with excellence is, one thing that really struck me is you really got this notion from both Rachel Carson and Abraham Lincoln, if you want to pick two extreme folks, that when they thought that things were messed up, weren’t ready yet, they would slow down until conditions were right or things were right in their mind. They’d do the research, they’d create the allies, this idea of slowing down to get things right, again, to stop you from doing bad things.

Rachel: I think what strikes me about the examples you’re giving is this sense that effective leaders are able to recognize that they can’t do it alone. And when there are moments of uncertainty or real fear, and in Shackleton, it’s like a real–

Bob: You’re gonna die.

Rachel: We could die.

Bob: Right.

Rachel: In times of great unpredictability, slowing down and getting kind of your troops or your staff or your team to just feel like they have one piece of solid land seems so important to getting anything done.

Bob: And in that message, so that idea of slowing and resetting and all, getting on the same page, there’s also this notion, which comes out in a lot of the research, that when people are exhausted and frenzied, they actually get stupid. We reviewed some of the research.

Rachel: That rings true

Bob: Yeah, that rings true to me, too. The more harried I am, that’s the opposite of flow, the dumber I get.

Rachel: Okay, so I wanna ask you a question about that. We’re in this super fast-moving world. Everyone’s afraid someone is going to out-compete them, outgrow them, get like, what would you tell our listeners to help them feel okay about slowing down and not rushing?

Bob: Well, I’d tell a story. This is one of my favorite stories, an argument for slowing down. So there’s a piece of software now everybody knows, Waze, or most people know Waze famous navigation software. So there was a point right after they got Series B financing, they got $30 million, and when you get Series B financing, our listeners who are active in Stanford Technology Ventures Program and eCorner will know, that means that you’re supposed to hire people and do more product development. But what happened was that the CO, this Israeli company, they figured out that whenever people would download Waze, a month later, none of them would be using it, so they had a real serious problem.

Rachel: Wow.

Bob: So even though he was under all this pressure to develop the product and to hire a bunch of people, he had everybody in Israel and the United States, an Israeli-based company, just slow down and spend six weeks, talk to users, do some analysis, and figure out what was wrong with the product and why nobody would keep using it. And they figured out what was wrong for full six weeks, and then, once they figured out what was wrong, and they made this MIT list, most important thing, rank-ordered list, then they hit the gas and they started moving forward. And to me, that’s almost the perfect example of what happens when you hit the brakes for a while and then you hit the gas and go faster. But I think that’s a pretty good example that sometimes you gotta figure out what the heck is wrong. And the other thing, as we heard in Jeff Pfeffer’s episode, where if you work people like crazy and work them really long hours, that eventually they’re gonna wear out on you. They might get sick, they might sue you. There’s a whole bunch of other more practical reasons, too, you might wanna slow down a bit.

Rachel: So there’s something there about whether it’s humans as resources or capital as resources or time as a resource that, if you’re about to spend a ton of it doing something really fast, you better make sure it’s right.

Bob: And we’re seeing this now with both Facebook and we saw it with Uber some, that there’s a point, and Huggy and I actually call this debt, in some of the stuff we’re doing, friction debt, technical debt, cultural debt, there’s a point where you can speed up, but the problems sort of build, and if you don’t slow down and fix them, you’re gonna have all of this debt that you’ve sort of gotta fix. So that’s the other sort of element of this, that sometimes you can speed up for a while, but you eventually gotta slow things down or you end up in the situation where Facebook was in, where they probably went along too fast with their Move Fast and Break Things, and now they’re going back and they’re trying to go back and fix things. In fact, the new CEO of Uber, there was a story that just came out with him in Wired, and it was “Move Slow and Build Things.”

Rachel: I love that.

Bob: How’s that for a startup? So there’s this point where there’s gonna be some debt and you gotta hit the brakes.

So another advantage of making things harder for people to do than is necessary is that the harder you work at something, the more you will value it independently of its actual value. And there’s all sorts of research on this that shows that if we just keep, you know, it’s sort of like long-term relationships. You just keep throwing yourself at it. You’ll get more and more committed, for the most part, and the classic research here, one of the authors is the famous Dan Ariely who’s a famous psychologist, and Dan Ariely and some of his coauthors did a series of experiments with Rubik’s Cubes and especially, they called this the IKEA Effect, where what they figured out was essentially, the more effort that people would put in their damn Ikea furniture, the more they would pay for it. And essentially they had conditions where people built the entire piece of IKEA furniture, they built part of it, or they built none of it. And the more effort they put into building this stupid piece of IKEA furniture, I think it was a box, the more of their own money they were willing to pay to buy the box. It’s the same box, right?

Rachel: Wow.

Bob: And so to me, that’s a pretty good analogy of this notion that if you want to make people work for it, that they’ll become more loyal.

Rachel: So when we think about employees and organization, what are some ways to get them to get some skin in the game?

Bob: Well, so the classic things that organizations do, Google has calmed this down a little bit, but the more interviews you do for a job, the more you will value it independently of the quality of the job. The more brainwashing and more you suffer, the Navy SEALs would be an example of this and any military organization-

Rachel: Wow.

Bob: The better off it’s going to be. One of my friends who I’ve written about, Becky Margiotta, Becky Margiotta describes being a West Point plebe. This is in the ’80s, this was a long time ago. She was one of the only women, and you know, every day, somebody would get an inch from her nose and scream at her for 20 minutes for various reasons. And when you go through something, and you know, physically, they’d push her toward an absolute limit. They’d be running all, and that’s a kind of thing that she put so much of herself into that, that independently of what it meant to be an officer in the US Army, and she was very successful, she went into black ops and dark ops and did all these things she can’t tell me about, but independently of that, all that effort that she put into the US military made her more committed, and that’s how every military in the world sort of works. They run people through hazing. So another advantage of friction that we haven’t talked about quite so much, but one thing you can do with customers especially is if you can get them in a situation where it’s a little harder for them to get in and out of your store or in and out of your website, you can show them more stuff to buy. Back to IKEA, which we’ve already discussed, that’s the whole logic of an IKEA store. Try getting in and out without seeing a bunch of stuff. That’s part of the logic. They’re the masters of positive friction for better capitalism, I guess.

Rachel: That is a game that my wife and I play. It’s like, can we get in and out in 20 minutes?

Bob: In IKEA?

Rachel: Yeah, it’s, we’ve never won that game. I think so much of what you’ve been talking about is there are rational elements to The Friction Project and finding solutions, and there are emotional elements. And so I wanted to ask you two new magic wand questions.

Bob: Ooh.

Rachel: If you could relieve a fear or concern from every employee in the workforce magically, with your magic wand–

Bob: Ooh.

Rachel: What would you try to take away from them, and maybe it’s the feeling or maybe it’s a source.

Bob: So I think it’s a feeling, but it’s related to a source that management is often responsible for, which is that all of us go through periods where bad things do happen, but the worst part is the uncertainty where you’re waiting for the other shoe to fall. And this goes back, actually, to old research by Seligman, famous researcher in the happiness area. It’s the signal safety hypothesis that one of the reasons that the people in London could tolerate the constant bombing during World War II is they had a really good set of air raid warnings and really good radar on the coast, so when the sirens weren’t blowing, they felt safe. And when they went off, they would go down into the tube and they’d sort of hide, so the signal safety hypothesis. In so many of the places that we work, all sorts of bad things can happen. People can get laid off, there can be pay cuts. There can be demotions, bad things happen in life and sometimes they’re necessary. But to the extent that people who lead other people can tell them, you are safe for a while. Nothing bad is going to happen. I saw this in my early research in layoffs. The companies that would do the best sort of layoffs, they’d do a deep layoff and they’d say, we can’t make any promises about the future, but we promise that no one will lose their job for three months. And that way, people could go to work for 89 days knowing they had a job. And that idea of finding ways to create predictability for people where predictably is necessary, I think it does reduce that constant load and vigilance that just wears us all out, wondering what’s bad is gonna happen tomorrow. And obviously managers can’t control everything. I mean, accidents and horrible things happen, but there’s some things they do have control over.

Rachel: Now I love that, just some sense of, and especially because things are becoming more and more chaotic and more–

Bob: Ah!

Rachel: If you can just create something where you say, for the next five minutes, this is what’s gonna happen and it might– And I mean, I can imagine

Bob: Five minutes!

Rachel: it must be terrifying for a leader to go out there and feel like, well, somebody’s gonna think I don’t know my shit, or I’m gonna lie, or I’m gonna be sued ’cause I said this.

Bob: Right.

Rachel: But being able to own up to something with honesty and transparency, even if you can’t talk about the rest, gives people a sense that you’re a real human being and they have something they can count on, that’s cool.

Bob: And a lot of times, and I had this in some of my own superior-subordinate, where I’m a subordinate relationship with Stanford, a lot of times, I realize that the people who lead me will assume that I know that there’s some bad news coming or I’m doing something wrong, and I actually have no idea at all. Or that I’m completely okay and I’m safe, there’ll be no information about that, either. So just telling people, you’re okay and nothing bad’s gonna happen to you, that sort of predictability is one of the most important things. So what this reminds me of, I don’t think this is friction and I wrote about this, is there’s a guy named Joel Podolny. Joel Podolny is actually at Apple now. He’s head of Apple University and for some years was head of human resources there. But I knew Joel when he was a 36 year old, 37 year old boy wonder dean at the Stanford Business School, and I remember Joel used to say to me that when faculty came into his office and they said they were gonna leave Stanford because they were upset by the pay, the first thing he would do is spend five minutes telling ’em how much he loved them and how much everybody loved them. And he said that about 75% of the time, that was usually the problem was they didn’t feel appreciated.

Rachel: Wow.

Bob: And I think about that, it’s such a basic human need to have people to tell you that you’re appreciated, so I don’t know what that has exactly to do with friction, but I think that people are less paranoid and they don’t have to do all the stuff that Patty McCord talked about last season where the sneaking around and being paranoid and wondering what’s going on, if they just get it straight from somebody who maybe has some power over them.

Rachel: You still have a magic wand.

Bob: Oh, my gosh, you’re making me work, Rachel.

Rachel: We did the subtraction, so now we’re gonna do addition. So if you could add a fear or a concern that every leader would have to pay a little bit more attention to–

Bob: So this actually–

Rachel: What would you do?

Bob: If we’re in the world of friction, and I’m stealing this from my buddy Perry Klebahn, who I teach with at the Stanford d.school and he was a real executive. Well, his last job was CEO of a company called Timbuk2, which makes messenger bags, and a quite successful entrepreneur. And so what Perry talks about is the cone of friction. So what he means-

Rachel: This is so good.

Bob: -by the cone of friction is that executives, as they sort of travel through life, they don’t realize that they’re accidentally doing things to make things difficult for the people who work for them. And the little story I like to tell about this, and this is a CEO of, well, let’s say a Fortune 10 company or really big company, and it’s this story I heard about somebody who worked with him in sort of an administrative role for years. And so during an early meeting he went to, it was a breakfast meeting, and he just looked around, and he casually said, “There’s no blueberry muffins. “I really like blueberry muffins.” And he just didn’t mean anything by that.

Rachel: Oh, no.

Bob: And he sort of just threw it out. From then on, wherever he went, people would make sure there were blueberry muffins, and about a year and a half later, he said something like, how come everywhere I go, there’s so many blueberry muffins? And it’s sort of the cone of friction, that they’re watching you really closely. And sometimes they call this executive amplification, and executives complain about not having enough influence in resistance to change, but they also, there’s this thing called asymmetry of attention, where people who have more power are watched more closely by people who have less power. And you even can look at research on baboon troops. So it turns out, if you look in baboon troops, that the average member of the troop looks up at the alpha male every 20 to 40 seconds, because the alpha male-

Rachel: Wow.

Bob: -can hurt them or help them, right? And that’s sort of the way that us primates are in hierarchy.

Rachel: That’s amazing.

Bob: So as an executive, you gotta be really careful of that amplification or Perry Klebahn’s cone of friction and things like that happen all the time where executives will send out weak signals that get overly amplified that lead to all sorts of friction, cost all sorts of money. And they don’t even realize it’s happening, ’cause they’re just sort of blind and onto the next thing.

Rachel: So what do we do? Like what would help leaders be more aware? Should they complain less? Should they be more aware of that?

Bob: Well, so a lot of this, to me, the basis is about self awareness, so this is finding out some way to experience what it’s like to work for you or to have people in your life who can tell you when you’re screwing up. And one of my favorite examples of this, and this actually reminds me of a little consulting gig that Perry Klebahn and I did about four or five years ago, and Perry’s very clever about figuring out ways to sort of goad executives and to make them uncomfortable. And what this was, it was actually for Del Monte, so Del Monte sells canned goods to grocery stores all over the place. So he had the group of about 40, all guys, there was one woman, so it was like 40 guys and one woman, and they ran or owned large grocery store chains, large to medium-sized grocery store chains. And so what Perry did was he had their wives, remember 40 wives, one husband, shop at the grocery store chain of their spouse, mostly husbands, and point out things that were screwed up. The wives just kicked the shit out of them. They absolutely, and you know, they just had to take it. Why do you have this endcap? Why is the technology so difficult to check out? How come the bread, how come I had to bend down so low? The butcher was so rude to me. And it just went on and on. And the thing that I love about that is that, to find people in your life who can tell you the truth and to be able to listen to them, is really a precious thing.

Rachel: I wanna talk about hope. I’m getting real soft in the last episode, but friction is so much about frustration and tension. I just wanna know, very simply, why should we have hope about the future of the workforce?

Bob: Wow, wow, even though, if we listen to Jeff Pfeffer’s episode, we might get overly pessimistic, I think there is a lot of reasons for hope, and some of them, to me, when I think back to the various episodes, I think of Nancy Koehn and the amount of courage that people had, everybody from Abraham Lincoln to Rachel Carson. And in those situations, Abraham Lincoln and Rachel Carson are actually interesting cases where, when things seemed darkest for them, things always got better. Well, they both died in the end, but everybody dies in the end. That’s why we have to be pessimistic. But in terms of their great accomplishments in life, both of them went through dark periods where things got better. The other reason to have hope, and honestly, it just amazes me. I went to graduate school at the University of Michigan and I first visited General Motors, and I remember going and meeting with the head of HR, who I thought was a pompous idiot. This would have been in about 1979. And General Motors has gone through ups and downs, but the most amazing thing is they’re not only still alive, they’re actually one of the most innovative automobile companies on the planet. It’s just, it’s sort of amazing what they’re doing. Oh, we taxpayers did bail them out, so thank you to all of us in the United States, but the conversation with Michael Arena really showed a lot of sophistication of this organization that’s been on the ropes and almost died just a few years ago and how much it’s coming back. And a lot of it has to do, and I wrote an old post about this, I argued that their core competence used to be, no, we can’t. And I worked with them fairly deeply right before they went into bankruptcy, that I heard their core competence was arguing why they couldn’t do new things. And I think because they went so close to death that it’s actually really quite impressive, their ability to be agile, to get out of markets when it doesn’t work anymore, as Michael discussed, to start new product lines, to be really one of the leading manufacturers, with the Volt, of plugins. You know, everybody keeps waiting for the great god Tesla, but meanwhile, they got a product out there that actually works and they actually might even make some money on. And so General Motors does give me a lot of hope, and especially on the friction side, ’cause that’s an organization where I just couldn’t believe that they could ever learn how to move faster and how to get the most out of the smartest people, and they’ve done a great job and not really being dealt that great of a hand, either. They played a weak-ish hand really strong and now they’re a strong company again, I think.

Rachel: So what I hear from that is a lot about just the incredible capacity of organizations and individuals to be resilient, that you have to look darkness in the face and deal with it. And then I’ll tag it onto one of your mantras that I use, which I think is more optimistic, which is we shouldn’t be asking whether we’re succeeding or failing. We should be asking, what are we learning?

Bob: So yes, so yes, that is one of my mantras, and I think that General Motors and somebody like Michael Arena, in particular, gives us that attitude. So does my coauthor and friend Huggy Rao. That’s one of the things that I love about Huggy is no matter how screwed up things are, like I’ll start getting dark, and he always sort of says, isn’t this interesting? Isn’t this a great learning experience? And he’s absolutely fabulous in terrible situations, and I sometimes think that the more screwed up things are, the better he is in lots of ways, ’cause when everything’s going right, it’s kinda boring to him.

Rachel: And so in every team, you should probably have a good complainer to tell you when you’re really messing things up and somebody who’s just optimistic in the most awful of times. And maybe we’d all be a little bit better.

Bob: Well, wow, it’s always been the optimists and pessimists need each other and realist and dreamers, we all need one another, so I think that might be a nice way to sort of wrap things up.

Rachel: Bob, thanks for letting me hijack your podcast once more and for agreeing to do a second season of FRICTION. This was so much fun.

Bob: Rachel, thank you so much. It’s been a joy to finally talk to you on the air, and I’m looking forward to maybe even season three, let’s see. The season’s over but the work continues on The Friction Project. We appreciate all of you for listening. We appreciate those of you who have sent us stories, and we hope that you will continue to send us your stories, your suggestions, and your ideas, and thanks once again for everyone who’s joined us in this little adventure.