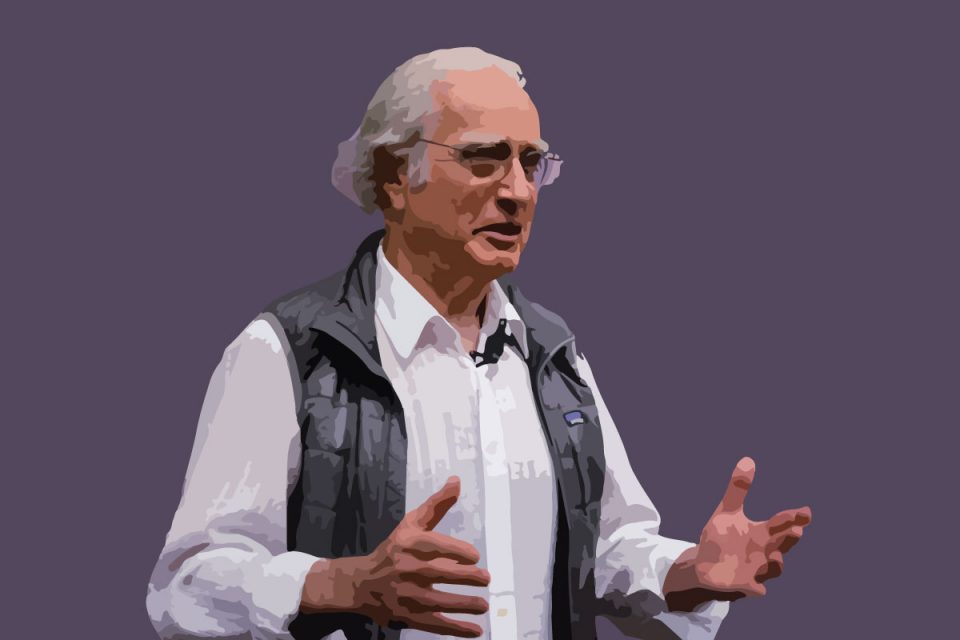

Stanford Engineering Professor Bernard Roth, a founding faculty member of the university’s renowned design institute, told audience members attending one of his recent talks at Stanford University how to “stop wishing, start doing and take command of your life.”

That’s the subtitle of Roth’s new book, The Achievement Habit, and he summed it up in terms verging on blasphemous to the science-loving attendees of the April 13 talk. He disputed the wrinkled, green Jedi’s famous line in Star Wars: The Empire Strikes Back: “Do. Or do not. There is no try.”

To that, Roth stated flatly, “Yoda was wrong.”

Risking the wrath of sci-fi fans everywhere, Roth explained that there is indeed a “try” and a “do.” “There’s really nothing wrong with trying to do something, and there’s certainly nothing wrong with doing it,” he said. “The problem is when you think they’re the same thing.”

That assertion is at the heart of Roth’s teaching over the past 40 years, at Stanford and in workshops around the world. Initially offered as classes in creativity, Roth’s teaching has grown to encompass all that goes into “design thinking,” which is rooted in engineering’s focus on building solutions to problems and involves human-centered need finding, prototyping and iterating.

More commonly known on campus as “Bernie,” Roth is a Jedi in his own right. He is the Rodney H. Adams Professor of Engineering at Stanford and is a longtime veteran of the university’s design scene, first joining the faculty in 1962. He has a worldwide reputation as a researcher in kinematics and robotics, and his most recent activities have moved him more strongly into experiences that enhance peoples’ creative potential through the educational process.

Roth currently serves as the academic director of the d.school, known formally as the Hasso Plattner Institute of Design at Stanford. It has become a hub for innovators throughout campus, where students and faculty in engineering, medicine, business, law, education and the humanities converge “to take on the world’s messy problems together.”

At his talk for the Entrepreneurial Thought Leaders Seminar (MS&E 472), Roth acknowledged that his current thinking seems to run contrary to the ethos of design thinking, which focuses on the problems of others, not the ones doing the thinking. But let’s face it, we all have problems — and Roth was intent on proving that the tools for unlocking solutions that he has developed would work for everyone in the audience.

In keeping with his emphasis on “doing,” rather than simply talking, Roth showed attendees how to reframe problems in a way that increases what he called the “solution space.” He told audience members to:

- Think of a problem in your life.

- Ask yourself what solving that problem would do for you.

- Turn the solution into the question you need to answer.

For instance, one person told Roth that he is slow to get out of bed in the morning. And when Roth asked him what getting out of bed would do for him, the man said it would allow him to get more work done during the day.

“So the question is how to get more work done. It has nothing to do with getting out of bed,” Roth replied. “I can figure out a way to stay in bed and get more work done, as an example.”

In his book, he calls this “moving to a higher level,” and he applies it to profound problems that everyone faces. He starts with the question “How might I find a spouse?” and then turns it into a declarative sentence that sounds more like a challenge: “Find a spouse.”

He then asks, “What question is ‘Find a spouse’ the answer to?” This unlocks a long list of possibilities, including:

- How might I get companionship?

- How might I get taken care of?

- How might I stop working?

- How might I have (more) sex?

“Each of these questions, regarded as a problem, has many possible solutions,” Roth writes in <The Achievement Habit. “Finding a spouse is just one solution to each of these. In actuality, it may not be a very good solution to any of these problems.”

However, Roth also cautions that doing isn’t always a virtue, and in his book, specifically calls out Silicon Valley’s obsession with change. In this high-speed, hyper-competitive business environment, companies are always doing something new out of fear that they will stagnate and fold without constant innovation.

The problem, Roth writes, is when we let that notion rule our personal lives.

“Often the things we strive for only represent more of something we already have: money, fame, appreciation, love,” he explains. “It’s an endless chase; as the saying goes, you can’t get enough from more.”