For the past few years, I have watched the news coming out of Silicon Valley closely. As someone who has spent the last four decades living, working and teaching in the San Francisco Bay Area, this might seem only natural. But as a former tech executive and entrepreneur who has taught entrepreneurship and innovation at Stanford University for almost 25 years, the news, especially the reports of scandals and wrongdoing, feels personal. Perhaps the news feels personal in part because I know some of the tech execs being written about. I have increasingly wondered what role I, as an entrepreneurship educator, play in this ecosystem as the news reports pile up and become so substantial that they can sustain book-length works.

To read such accounts about entrepreneurs shook me to a point of realization. For years, I have espoused the value of teaching every student to have an entrepreneurial mindset, and now, I must do better, as an educator, to help address the factors — both systemic and personal — that lead to these headline-making incidents.

In early March this year, I met an educator asking similar questions. At a UNC Chapel Hill business school lunch, philosopher and Professor Geoff Sayre-McCord introduced himself to a table of entrepreneurship educators and administrators by saying, “entrepreneurs face a moral liability: that they will become liars.” It was a bold remark to make in a business school setting, and I was intrigued.

What does principled entrepreneurship mean? Can it vary per entrepreneur? Are there any immutable principles for entrepreneurs?

For decades, I have taught my students how to dream big, secure funding, gather a team and entice customers and beneficiaries by crafting a promising vision of the future that is only tenuously based in fact. Certainly not all entrepreneurs are liars, Sayre-McCord clarified for me in follow-up conversations, but many of the incentives an entrepreneur encounters encourage deception.

Sayre-McCord’s point left me wondering: Is there a fundamental design flaw in the discipline of entrepreneurship education? Is believing in and selling a future vision all good or all bad for society? Is it time to shift the way we think about the role of ethics in entrepreneurship education?

As a faculty director of the Stanford Technology Ventures Program (STVP) since its inception, I have witnessed entrepreneurship education explode into a vast multitude of university-wide offerings. In terms of the pedagogy and content itself, entrepreneurship education has made great strides in the last three decades: educators have refined curricula based on empirical and theoretical research and broadened the discipline’s scope from early-stage startups to large organizations. Now, I believe it’s time for another shift for the coming decade.

With accumulating reports of wrongdoing, educators must take action to confront any systemic failings. We must equip our students, the next generation of entrepreneurial leaders, with frameworks for principled entrepreneurial action and knowledge – or more simply put, a tool kit for action-oriented practical ethics.

A Budding Discipline

For the last 25 years, I have been an advocate for expanding opportunities and offerings for entrepreneurship education intended for all college students. My passion for entrepreneurship education began with working in Silicon Valley in the 1980’s and early 1990’s after completing an MBA and Ph.D. at Berkeley. I had seen how new enterprises with new technologies could dramatically transform business-as-usual for the better.

During the formation of Symantec Corporation, I witnessed how software could safeguard sensitive information stored on the nascent personal computer and its networks. I eventually left Symantec after its IPO to co-found another venture producing software applications for early tablet computers with Dan Bricklin, an industry icon and highly principled inventor of the original spreadsheet program. In 1995 during the emergence of the Internet, I joined the faculty at Stanford’s School of Engineering full-time feeling quite optimistic about the power of entrepreneurship and technology to change the world.

In the mid-1990’s, entrepreneurship courses were confined to business schools as second-year electives for MBA candidates. Our mission at Stanford became to ensure that entrepreneurship courses would be available to every student, regardless of their major or school of study. So we founded STVP, an academic center for developing and spreading entrepreneurship education to all students at Stanford by operating within the Department of Management Science and Engineering.

The next two decades were exhilarating. To foster a community of teachers and scholars focused on entrepreneurship and innovation, Professor of the Practice Tina Seelig and I organized almost 50 roundtables on five different continents. We became allies with entrepreneurship educators at other universities to bolster our fledgling discipline. Accomplished scholars and esteemed practitioners including Professor Kathy Eisenhardt, Professor Bob Sutton and Adjunct Professor and serial entrepreneur Steve Blank joined us to develop curricula to teach the skills and behaviors of an entrepreneurial mindset. We saw students harness their creativity, critical thinking skills and technological capabilities to build new products that were helping solve the world’s most challenging problems. We worked continually to improve our teaching methods and curricula, making our discipline deeply grounded in empirical and theoretical research as well as expanding our lessons beyond small startups to large enterprises in business, education and government.

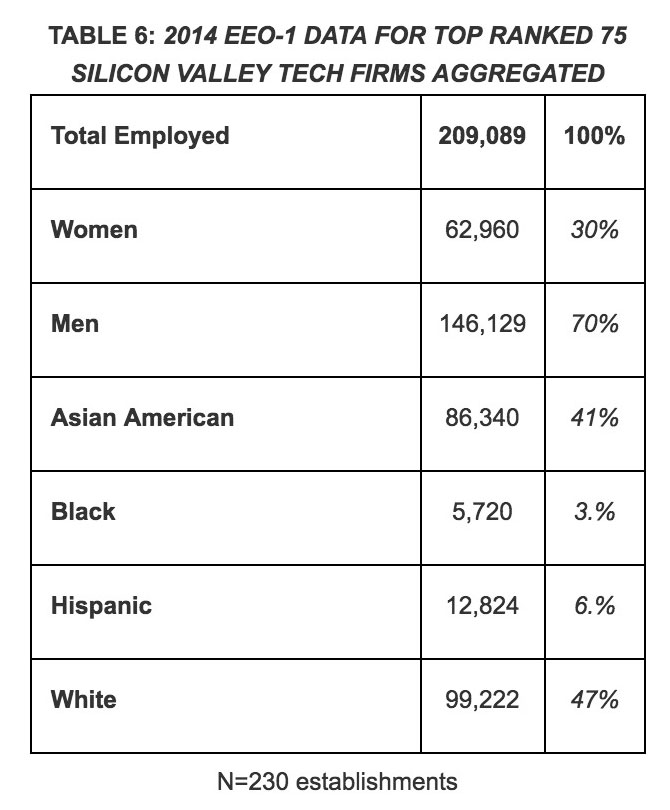

The message caught on even more quickly than we and our peers had expected it would. In about two decades, entrepreneurship education moved from a few MBA elective courses to a core university offering, both nationwide and around the globe. And entrepreneurship, especially entrepreneurship in the technology industry, has seen a similarly swift rise to prominence in all facets of society and the world’s economy. Venture capital investments in early-stage companies has increased nearly sixfold in the US during that period, and according to a recent industry analysis, the American tech sector employs over 11 million people and contributes an estimated $1.6 trillion to the US economy. The result of tech’s rise has been many spectacular services and products, and sadly, the numerous scandals we have seen play out in recent years.

Room for Growth

Today, Stanford entrepreneurship faculty teach well over 100 courses per year. We educate thousands of students in every corner of the campus, teaching them the essence of an entrepreneurial mindset. We cover things like the importance of adaptability, opportunity recognition, resilience, leading teams and creativity. We give them frameworks that help ground debates about when to take risks. We train them to gather data like a scientist doing lab experiments. We push them to practice again and again to get comfortable with failures. We encourage them to be solution-oriented in the near term and opportunity-minded in the long term in order to scale their creations for maximum impact. We consider concepts like product-market fit and how to create business models that will entice investors and attract customers and partners.

Sometimes, though, students are interested in discussing the more personal, less positive aspects of entrepreneurship. Perhaps compelled by the same news stories that leave me feeling so concerned, they ask about how they should navigate ethically difficult situations in the future when working at a startup, when investors bear down on them, when founders breach ethics and when a colleague behaves in an unprofessional manner. With questions like these, I always find myself searching for better answers.

Because of classroom situations like this, I along with a few dedicated colleagues have spent the past year researching how values and ethics can be better taught in entrepreneurship courses. I am encouraged by the existing models for mission-driven organizations available in the field of social entrepreneurship. I am emboldened by the comprehensive scholarship and teaching of ethics programs that serve all students. I find further confidence in the conversations we’ve had with ethicists at law, medical, business and engineering schools. Those specialties in professional graduate schools began offering ethics courses long ago.

Our mission at Stanford became to ensure that entrepreneurship courses would be available to every student, regardless of their major or school of study.

Our goal is to create classroom environments that encourage students to establish their own principles-based worldview. What if each student creates their own personal mission statement, to define for themselves the values that will guide them? But to do that I have first have to ask questions of myself as an educator. I must find some approximate answer to questions like: What does principled entrepreneurship mean? Can it vary per entrepreneur? Are there any immutable principles for entrepreneurs?

A Different Kind of Value Creation

When teaching ethical behavior in my own classroom, I have found success using role-play simulations with students. For many years in the first course of our Mayfield Fellows Program at Stanford, the source of our simulation was the “Randy Hess” case study, based loosely on the MiniScribe fraud case of the 1980s and developed by the distinguished author Jim Collins. Students prepare by reading the case and during class, a student would volunteer for the role of “Randy Hess”. While some other students took on the role of other employees at the startup and its audit firm, I played the role of of the unethical CEO.

As that CEO, I would try to persuade the student playing Hess, a member of the finance department, to remedy a revenue shortfall with an illegal “adjustment” to the accounting records. Coming into the class, students were certain that they could not be compelled into doing something they know to be wrong. Then the roleplay would begin. As the CEO, I would use various negative influence techniques. If necessary, I even threatened (falsely) to give the student a bad grade in the course. The environment in the class would become tense, and more often than not the “Randy Hess” student relented. We would stop the case and talk about ways to protect yourself from the negative forces of influence and persuasion. They understood the importance of the conversation. The students had just seen how most everyone, even in role-play simulations, has a breaking point.

Role playing is the method I choose, but the material about motivation and persuasion comes from the work of psychologist and Professor Robert Cialdini. In his bestselling book Influence, Cialdini lists the six factors of influence: reciprocity, scarcity, authority, consistency, liking and consensus. In the Randy Hess role play, I would offer to do something nice for the student playing Hess and then ask for adjusted books in return (reciprocity). I would tell the Hess student that everyone does things like this sometimes (consensus). I’d appeal to the idea of Hess’s personality and sense of duty, suggesting that adjusting the books would make sense since “he’s the kind of guy who would help his company in a hard time” (consistency).

This exercise in teaching applied ethics, though, focuses more on not doing something unethical than envisioning a positive set of values. Though this model may not map perfectly onto secular educational contexts, I am intrigued by how students are urged to define and form their own codes of conduct within the entrepreneurship school at the University of St. Thomas, a Catholic school in Minnesota. There, Professor Laura Dunham and her colleagues promote the value of “practical wisdom” — essentially, pursuing entrepreneurial projects while considering how a given project will affect its consumers and stakeholders. For Dunham, entrepreneurship isn’t amoral and at St. Thomas, entrepreneurship is taught as a way to create value beyond the financial kind.

A mindset like the “practical wisdom” framework taught by Dunham can be crucial for first-time entrepreneurs entering the current venture environment, where the perceived need for “speed” in building a new company can outweigh the need for building stakeholder trust. For startup founders looking to deliver on proposals made to financial backers, it can be easy to consider very little besides developing the product, without articulating a core set of principles and the company’s relationship to its clients and community.

I see this same kind of desire to consider entrepreneurship contextually in the venture capitalist Chi-Hua Chien. Chien uses a model called the “five critical risks of entrepreneurship”: market, team, technology, product and business model. But after using this model for several years, Chien has suggested that we add a sixth risk: values. As someone who leads a fund that invests in early-stage companies, he believes that venture capitalists benefit when they consider founders’ guiding principles. Sussing out principles can give investors a better sense of how founders will act in difficult, murky situations.

These aren’t one-size-fits-all recommendations, but I share them because I believe these models illustrate a way of thinking through the problem of how to teach principles and entrepreneurship. It seems to me that creating new teaching materials will mean teasing apart a few entwined threads:

- First, we must consider what it means to have values and teach them in a secular, nonpartisan way.

- Second, we must look at what methods best teach students about themselves in particular and entrepreneurial projects in general.

- Third, we must consider the unique aspects of the entrepreneur’s environment, from a variety of investment structures, methods for experimentation and growth, and the cultural norms within different geographies.

Is it time to shift the way we think about the role of ethics in entrepreneurship education?

Re-Defining Entrepreneurship Education

Spending the past year researching applied ethics pedagogy has felt surprisingly similar to the first few years I spent at Stanford in the 1990’s, helping greatly expand the reach of the university’s entrepreneurship offerings and encouraging educators at other universities to do the same. As in those early years, I’ve had numerous conversations with others. More or less, I go to each asking the same question: Do you think ethics-related teaching materials can and should be improved in the entrepreneurship courses? The answer I receive is overwhelmingly a resounding yes.

In these conversations with educators, administrators, industry leaders and students, I feel an emerging groundswell — so many want to see innovation in the way educators teach entrepreneurial values. I hope that every educator, student, current and aspiring entrepreneur will join me in working to re-define entrepreneurship education, because it is crucial that students are equipped with the awareness, knowledge, skills and principles required to confront complex ethical challenges. Together, we must consider what educators haven’t yet done and what they can do to address this shortcoming in our incredibly vital discipline.